The story of the LWBL / CKC begins in the early 1870’s. Puget Sound was without a transcontinental railroad link and the tiny settlements on the shore were in fierce competition for the railroad terminus. Olympia, Steilacoom, Fidalgo, Mukilteo, Port Townsend, Bellingham, and Seattle were all in the running. Most believed that whichever community the Northern Pacific Railway (NP) chose as its terminus would become western Washington’s dominant city, so the competition was heated with communities trying to outdo each other in their offers to woo the NP and land the terminus.

In 1873 the NP chose the sparsely-settled Commencement Bay, Tacoma, for the coveted terminus—due in large part to the vast amount of available land that the NP could snatch up, in effect creating a new company town. This decision came as a huge blow to all the communities in the running and Seattle was no exception.

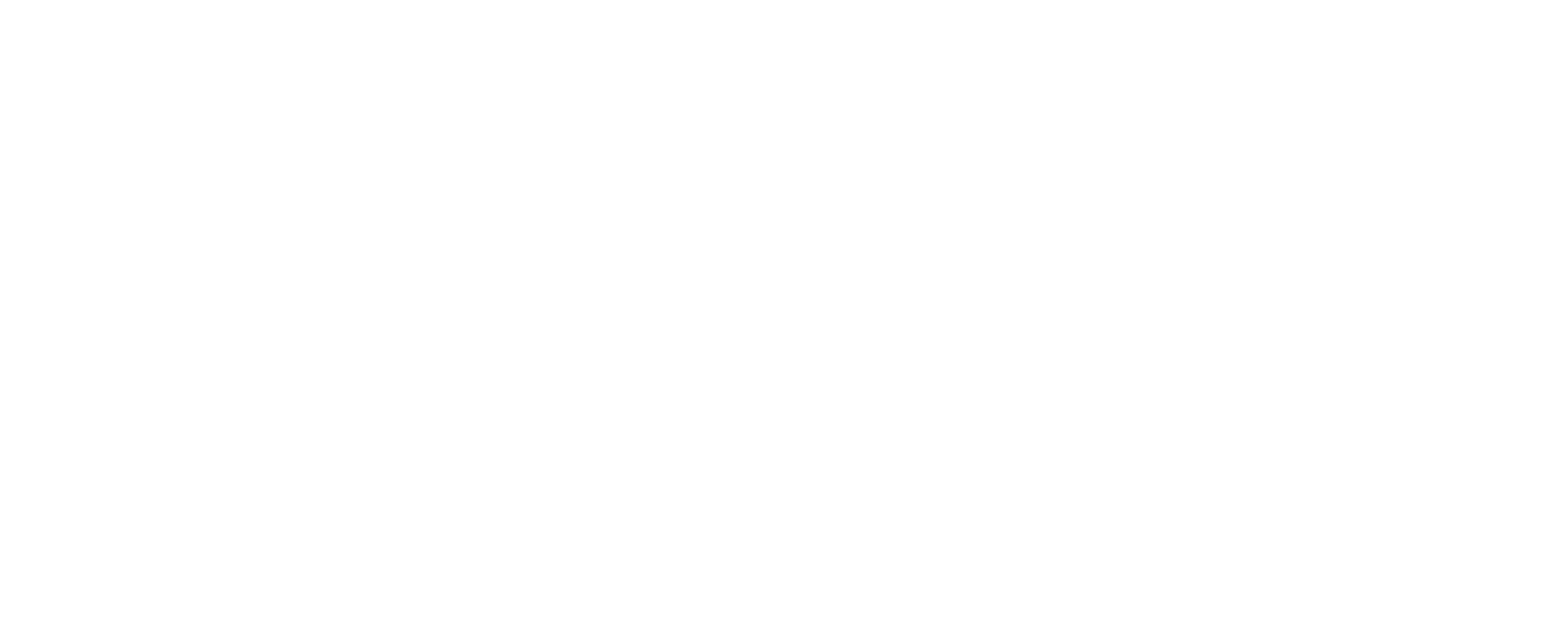

Upon completion of its surveys of Townships 25 and 26 North, 5 East, the Federal government had opened the eastern shore of Lake Washington north of today’s Village of Beaux Arts for homesteading in 1870. A land rush of sorts ensued as settlers snapped up homestead claims typically allotted in 80- and 160-acre parcels (Township 24 North, 5 East, to the south, had opened five years earlier due to the discovery of coal, near today’s City of Newcastle). The soil was primarily nutrient-poor glacial till, what geologists call “Alderwood loam“, and not terribly well-suited for agriculture. While there was some agricultural output, most homesteaders subsisted on their claims, which they called “ranches”, and many also had full time and seasonal jobs in Seattle. For example, Houghton settler Harry French, who came from Maine in 1872 and bought an existing claim of 80 acres on the lake, noted working in Seattle for “Mr. Yesler” in his journal. This reference was to the pioneer steam sawmill that was established by Henry Yesler in 1852, the year after the Denny Party founded Seattle. The crops that were produced required costly transport via wagon, transfer to a steamboat to cross the lake, and another 3 ½ mile wagon trip from the west shore of the lake into the still fledgling Town of Seattle, which in 1870 had a population of merely 1151 people.

In 1888, an investor group led by Seattle Post-Intelligencer newspaper publisher Leigh Smith James (S. J.) Hunt sought to industrialize the eastern shore of the lake. What is now the City of Kirkland was selected as the site of an ambitious steel mill complex and a company town, headed by recently-emigrated British steel entrepreneur Peter Kirk, Kirkland’s namesake. Railroads were then growing rapidly, resulting in a promising market for steel rails. At that time the tiny, unincorporated Juanita and Houghton communities were the only named communities between Yarrow Bay and Juanita Bay.

First rail service to Kirkland: The original LWBL

The Kirkland steel mill was to be built near Forbes Lake and it would require a rail link to supply needed raw materials: iron ore, coking coal and lime. Hunt and others formed the Lake Washington Belt Line Company, which sought to build a rail line from Black River Junction, very near the original Longacres race track, through today’s Renton, Bellevue, and Kirkland to Woodinville, where it would connect to the existing rail infrastructure of the Seattle, Lake Shore & Eastern Railway, an upstart affair that sought to build east and north from Seattle to connect to transcontinental railroads after Seattle was snubbed by the Northern Pacific. In addition to serving Hunt’s planned industrialization of the eastern shore of Lake Washington, the line would provide a bypass for north-south rail traffic that did not need to stop in Seattle, where substantial rail congestion existed by the 1890’s, which added considerable travel time for trains just passing through.

The Lake Washington Belt Line Company completed grading operations and began laying track simultaneously, north from Black River Junction and south from Woodinville, with the southern effort reaching as far as Renton and the northern crews reaching just south of the steel mill, where the Belt Line Company built a relatively elaborate two-story passenger and freight depot at about the intersection of today’s 7th Avenue / NE 87th Street and 116th Avenue NE. (This site was obliterated by the NE 85th Street interchange for I-405.) Kirkland was a literal boom town.

By 1892, financial downturns leading into a depression dubbed “The Panic of 1893”, political factors, and various other reasons brought Hunt’s Eastside industrialization and belt line efforts to a halt and the line was never completed. The steel mill structures were abandoned in their partially-constructed state, never smelting any steel, but the Woodinville-to-Kirkland tracks were used for several years to serve several lumber and shingle mills along the route.

Another casualty of the Panic of 1893 was the SLS&E, which went into receivership in June, 1893. Its lines in western Washington became the Seattle & International Railway Co. in 1896, which was taken over by the Northern Pacific in stages, and completely absorbed in 1901. The former Belt Line was absorbed at the same time.

Rail corridor revived: The “new” LWBL

As the years went by and the region made a slow financial recovery, the need for freight trains to bypass the congested Seattle rail terminal, especially Railroad Avenue on the waterfront, increased in significance, prompting the NP to revisit the belt line project. It concluded that bypassing rail congestion in Seattle and the benefit of providing Eastside agricultural producers cost-efficient transportation to bring goods to market justified reviving the effort to construct a north-south rail line through the Eastside.

The first step was to survey a new route, the money for which was approved in September, 1902. The NP adhered to the 1890 route for much of the distance, but in some areas deviated substantially, particularly through what is now Bellevue. South from Woodinville, the new line followed a new grade for about the first mile, then rejoined the 1890 grade into the Totem Lake area, and then diverged again. Where the 1890 route proceeded south along what is today Slater Avenue, the new line turned west, toward Totem Lake, and then turned back south west of today’s 405 and remained west of the 1890 grade until re-joining once again in the south part of Houghton. The new route through Kirkland followed a more gentle grade and put the tracks closer to the central business district.

LWBL construction

Construction of the new Belt Line was approved in February, 1903, at an estimated cost of $384,534.15 (roughly $11 million in 2018 dollars). Work on the 24-mile line was delayed by bad weather that stopped work for much of the winter of 1903-04. By August 1904, the Seattle Times reported that the engineering department “has abandoned all definite predicting” due to many completion dates having been set and missed. The contractors reportedly had trouble keeping an adequate labor force on the job. That same month, the NP authorized an additional $200,466.00 (about $5.7 million in 2018 dollars) to fund the remaining work, noting additional factors of unexpected landslides, restoring part of the old Belt Line north of Renton, and poor rock ballast quality.

The NP’s Construction Department turned over the line to the Operating Department in October, 1904, but the NP did not start using it immediately for regular service. The first listing of the Belt Line in an NP employee time table was not until June, 1905, indicating that about 18 miles of the line was open as a long spur, from Woodinville south to near Kennydale, rather than the complete route. NP documents indicate there was trouble with the roadbed sinking in this area, requiring extensive repairs, including 93 car loads of fill material.

Also during this time, the Operating Department was likely negotiating contracts with potential shippers along the line and installing commercial spurs, to help the line generate revenue. It is worth noting that the value of the Belt Line as a bypass for congestion in downtown Seattle was not fully realized until the NP opened a major terminal in Auburn in 1913, allowing it to dispatch north-south trains from outside of Seattle.

On September 11, 1905, the NP finally announced that the freight train to and from Sedro-Woolley would be re-routed over the Belt Line and would serve businesses along it. Two days later, the Seattle Times published notice of regular freight service beginning, along with a list of stations. On October 24, the Seattle Times announced that passenger service to Snoqualmie via Woodinville would be re-routed over the Belt Line beginning in late October. The NP published a proposed schedule change for Trains 5 & 6 on October 29 and released an updated time table for employees on the same day, listing the completed Belt Line, as well as freight and passenger service for it, including Kirkland.

Once opened, the LWBL right-of-way stayed constant; sections of track were not moved or re-aligned. Spurs and sidings came and went over the years, of course. Perhaps the most major construction activity along the LWBL was the surveying and then construction of a major sewer trunk line, beginning in 1959, by King County Metro.

Passenger service on the LWBL

As described above, passenger service on the LWBL began when it opened for service in October, 1905 (NP employee timetable 25A). Along the portion of the LWBL that is today’s CKC, there was initially just one passenger stop, at Kirkland (Piccadilly Street). In May, 1906, flag stops were added at Firloch and the J. D. Jones spur just east of Firloch (NP employee timetable 25B). In February, 1911, a flag stop was added at Houghton (NP employee timetable 33A). In April, 1913, the flag stop at Jones was removed (NP employee timetable 38).

NP maps show simple open platforms at Piccadilly Street and Firloch but do not show the same at Houghton and Jones. As described on the depot area page, the Piccadilly Street platform was removed when the depot opened in 1912.

Passenger service to North Bend was temporarily discontinued in July, 1922, and was made permanent in October (NP employee timetable 48A), which ended regular passenger service along the LWBL. However, special passenger trains, such as to the Puyallup Fair in 1947 and 1948, sometimes offered boarding in Kirkland, and Casey Jones excursion trains also passed by the depot from time to time in the 1950s and 1960s.

Freight service on the LWBL

Over the years that the LWBL was in operation, freight train service for Kirkland industries was handled by an assortment of trains, of both the “local” and “through” variety, depending on the priority of a given car’s contents. Normal-priority work was handled by local freight trains, whose purpose was to serve any and all industries within a given operating area. One local freight that served Kirkland for many years was known as the Woolley Local, which ran from Auburn Yard to Sedro-Woolley one day and back the next.

Higher-priority carloads were handled by freight trains that were passing through to specific destinations. For example, the Auburn-Everett Time Freight, which made the round trip in a single day, was known to serve Globe Feed and Seattle Door Co. in the 1960s. The highest-priority through freight, Train 675/676, which ran to/from Sumas, to connect with the Canadian Pacific and British Columbia Electric Railway, handled only critically-important carloads for Kirkland, under extraordinary situations.

Occasionally, regional and national events affected the relationship between the NP and Kirkland businesses. For example, in July, 1967, a rail strike “pinched” Kirkland industries, especially Seattle Door Co., which received about 85% of its raw materials by rail and shipped most finished goods by that method.

Trains from other railroads

It was rare to see trains from other railroads on the LWBL, except for highly-unusual circumstances that caused re-routing, such as a wreck or a weather-related closure. This changed once the Milwaukee Road gained a concession following the merger of the NP and Great Northern in March, 1970, forming the Burlington Northern (along with the Chicago, Burlington, & Quincy). The Milwaukee Road began running trains over the LWBL to Woodinville, then continuing on the NP to Snohomish and then into Everett on the GN. From there, traffic was forwarded via the GN to points north, such as Bellingham, Vancouver, and Sumas. These trains ended when the Milwaukee Road ceased operation in Washington in 1980. Long-established NP freight train patterns also changed following the merger—the through freight from Auburn to Sumas (BN Nos. 144 & 143) began running through Seattle almost immediately after the merger, but other, more local, freight trains continued to use the LWBL.

.jpg)

.png)