Firloch is the region north of today’s NE 116th Street to the Kirkland-Woodinville city limits. The LWBL runs close to the south side of Totem Lake, on which centered the area’s early industrial activity: shake and shingle production. The name “Firloch” is derived from the Firloch Mill, which operated on the lake in the early 20th century.

By Matt McCauley and Kent Sullivan

The area’s first settlers were Jesse and Sarah Spray. Jesse was born in Kentucky in 1811 and Sarah in Indiana in 1825, so they were older than most of the neighbors scattered around them on 80-acre parcels. They came to the Washington Territory via Iowa and the first record of them in the territory is 1877—the same year several other Juanita homesteaders filed claims, including the Forbes, Langdon, and Dunlap families. The Sprays purchased 80 acres and added another 80 acres via the Homestead Act.

The Spray’s farm was located on the west side of section 28, from Totem Lake to just west of today’s I-405. Jesse died in 1881 and the land was sold to a family named Wittenmyer, headed by George W., a carpenter, born 1831, and Annie, born 1841. The two married in 1857 and first appear in public records as residents of Seattle in 1880, having come from Wisconsin. The two had several children, including Walter, who became Kirkland’s first town clerk after its 1905 incorporation and George G., who went on to become King County Treasurer and was the center of a notorious scandal in 1934 when he vanished after about $35,000 of county funds were discovered to be missing. After giving assurances that he would clear the matter up, he was not seen again.

While today’s Totem Lake had several names prior to being legally changed to Totem Lake in about 1971, it was known for probably the longest period of time as Lake Wittenmyer.

.jpg)

.jpg)

Take a trip through time in Firloch

Picturing all of the changes in railroad spurs and roads over the 75+ years of development in Firloch is a tall order. We put together an animation to help you visualize the evolution.

Simply click on the image below to begin. You can click the animation at any time to pause it. You can also skip forward and back by using the progress bar at the bottom.

The aerial images from 1937, 1954, 1965, and 1970 are courtesy King County Road Services Map Vault. The 1959 aerial image is courtesy of the Northern Pacific Railway Historical Association and the 1981 aerial image is courtesy of the University of Washington Libraries Maps & Cartographic Information.

This is new technology for us, so if you have any difficulty, please contact us and let us know.

Note: There is no audio accompanying the animation.

Note: The full-sized video is also available.

J. D. Jones Spur

J. D. Jones, a Seattle-based attorney who specialized in maritime and admiralty concerns, contacted the NP in February, 1903 about shipping “a large quantity of timber, to-wit, several hundred thousand feet of logs, several thousand cords of [cedar] shingle bolts, besides a large quantity of cord wood”. How Mr. Jones came by this large quantity of wood products is not currently known. In any case, he asked the NP for a spur on the circa-1891 Kirkland Branch, but was denied, because the railroad thought that the 1891 line would soon be taken up, replaced by the Lake Washington Belt Line, so they asked him to wait. (Little did they know that it would be two more years before the new line was ready for service!)

The NP had approved a spur on the Kirkland Branch for Mr. Jones in June, 1902 and completed building it in July, so it’s a bit unclear why he contacted them again just seven months later about needing another spur (or possibly, moving the existing spur). Perhaps he hoped to have the “new” spur located at another point on the line, to minimize the distance his crew had to transport logs.

(As background information, the Kirkland Branch followed the route of today’s Slater Avenue NE south of NE 124th St. And, to make the situation a little more complicated, it was also originally known as the Lake Washington Belt Line, and was intended to serve the same function that the 1905 line eventually fulfilled. A variety of factors conspired to keep the line from being completed. It ran no further south than the unfinished steel mill atop Rose Hill.)

Mr. Jones kept in contact with the NP and filed a formal application for a spur in late May, 1904. The proposed spur was to be just over 250 feet long, to be located just west of where the LWBL crosses Slater Avenue NE today. Even at that late date, NP correspondence indicates that rails for the main track of the new Belt Line were about six weeks away from being laid, and, further, no spur tracks would be able to be considered until after the completed line was turned over to the Operating Department. By early October, Mr. Jones was quite desperate to ship his product.

Fortunately, the NP wrote him on October 31 that they, at last, had an operational line. However, unbeknownst to the parties of this conversation, officials higher up in the NP decided to delay opening the Belt Line for traffic until sometime in the Spring of 1905.

Anticipating a Spring opening of the Belt Line, approval for the spur came on February 22, 1905. In the meantime, the NP and/or Jones had moved the spur’s location slightly west and changed its orientation to face the opposite direction, perhaps to accommodate a length increase to 300 feet. Construction proceeded swiftly and the spur was ready for use on April 1 (an appropriate day for the long-suffering Jones).

A Mr. Christensen was apparently the operator for Mr. Jones, and he requested, just two weeks later, that the spur be lengthened to handle more cars. The “ever-courteous” NP replied that the projected long-term business did not justify the expense. As a side note, NP records also document the discussion and approval of removing a per-car switching charge of $1.00 for Mr. Jones, deemed appropriate given how long Mr. Jones had to wait for the spur to be installed. It was noted that the “new” Jones spur was the heaviest shipper on the Belt Line at that time.

In December 1912, NP personnel requested authority to remove the spur, saying it had not been used in three years and that other shippers in the area were using the “Firloch spur” (James Neel / Woodland Shingle Co. spur, below), about ¼ mile east. Authority to do so was granted in March, 1913 and it is presumed the track was taken up shortly thereafter. These dates nicely illustrate how rapidly a logging operation could exhaust the supply in a given area – four years or so in this case.

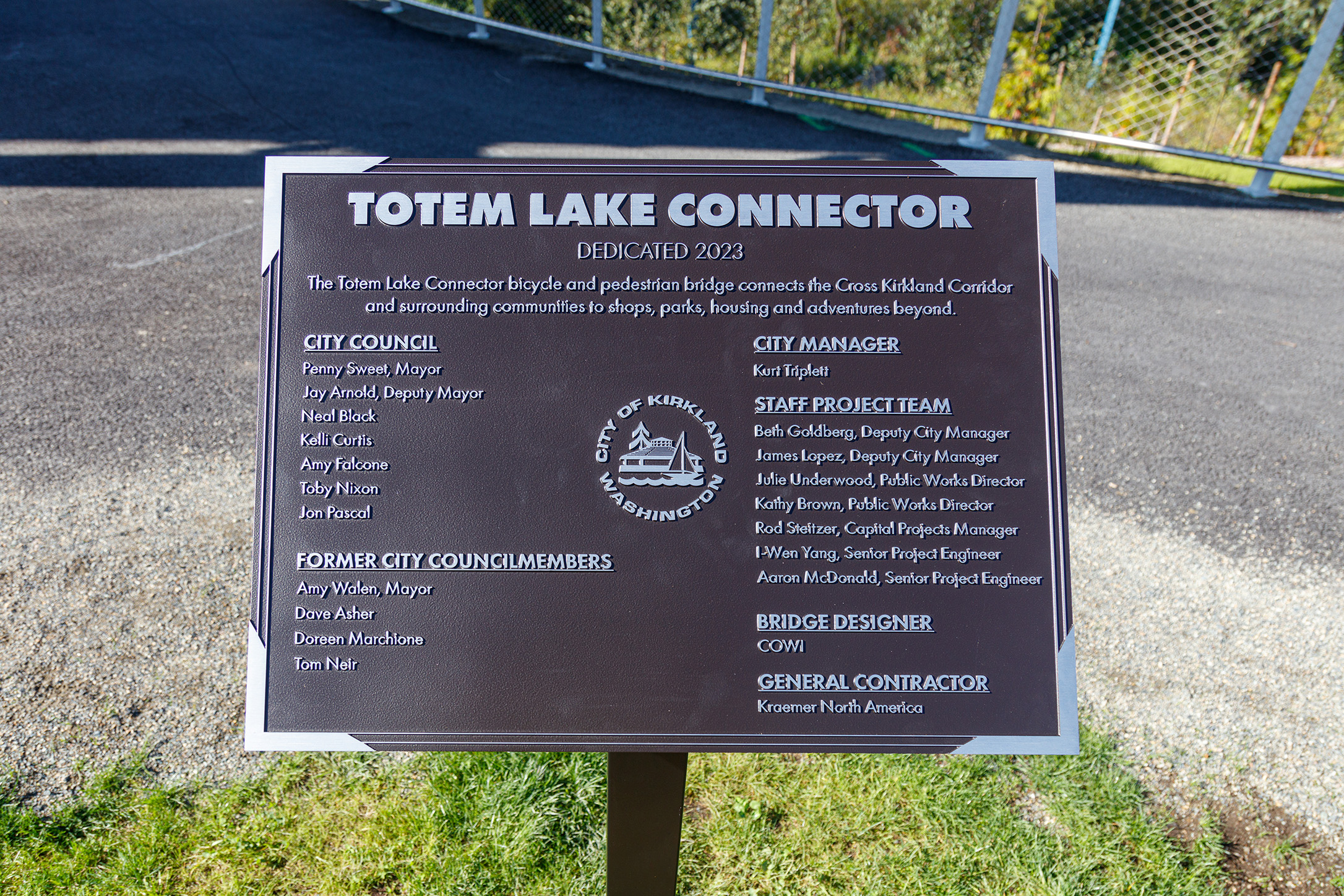

Robert Ficken, in his classic book on Pacific Northwest logging and lumber industry The Forested Land, observed on pp. 60-61, “From the beginning, shingle manufacturing displayed some significant characteristics. Only a small amount of capital was required and the industry tended to attract farmers, lawyers, and others whose desire for profit often exceeded their expertise.” Whether Mr. Jones is an example of this archetype is not presently known.

Note: As discussed in the History and Context of the LWBL section, the northern 17 (or so) miles of the Belt Line were in use as of June, 1905 (as documented in NP Seattle Division employee time table 25) and possibly somewhat earlier.

Firloch / James Neel / Woodland Shingle Company spur

Right on the heels of J. D. Jones was James Neel and his Woodland Shingle Co. Not as much paperwork survives for this spur as compared to the Jones spur, but it is known that a formal proposal was submitted in June, 1905, approved in July, and the spur was put into service in September. Less is known about Mr. Neel than Mr. Jones, although the former also had a downtown Seattle business address. The original location of the spur caused it to cross what is today’s Totem Lake Blvd. just north of today’s NE 124th St.

In January 1913, Neel petitioned the NP to move the entire spur 261 feet west, to remove the road crossing, and also to move away from a trackside gully. The request also entailed reversing the direction the track faced. Because Neel was a high-volume shipper (5 cars of logs per day, to log dumps in Kenmore and Everett) and because he offered to pay the cost, the NP approved the request, in April. The NP decided, at some point, to create a station (i.e., a named placed on maps and in timetables) on the line called Firloch at this location, very likely related to a mill named Firloch. It is not known at this time if that is a later name for the Neel / Woodland enterprise or a separate venture.

In June, 1921, NP officials in Tacoma asked local officials whether the spur was still in use, and the reply was “there is occasionally a car of wood or hay shipped”. The NP finally removed the spur in December, 1925.

Bridge 19

To speed the opening of a new piece of track, the NP would often construct wooden trestle-type bridges over low-lying areas during initial construction, filling them in later, with tons of dirt and ballast, after the line was operational. In some cases, the filling could not even wait until the line was open. The NP filed paperwork to partially fill it in January, 1912, because “this portion of Bridge 15 is in such condition that, in order to safely carry the track, the bridge should either be soon renewed or the opening filled” and noted that the “bridge was partially filled during October and November 1904” which is well before the Belt Line opened for regular service. The paperwork also stated that the work was practically finished already, having proceeded under emergency authority of the General Manager. Other paperwork in the file confirms that the work was finished in February, before being formally approved in March.

Note: In this paperwork, the bridge is numbered 15, which is a sequential count from the beginning of the line south of Renton, instead of 19, the system adopted later of numbering based on the nearest milepost. Also, a portion of the bridge remained after this work. It is not currently known when it was completely filled in.

I-405 overpass and crossing safety Improvements

In July, 1968 the NP approved a proposal to complete railroad bridge work in support of the State constructing an overhead bridge for I-405 over the railroad.

The NP installed two sets of flashing light signals, at Slater Avenue NE in October, 1964 and NE 124th Street in August, 1965. The Burlington Northern installed a grade crossing and flashing light signals at 124th Ave. NE in February, 1972 and added cantilever arms in May, 1978.

For more information, see the Collisions between Trains and Automobiles and Resulting Safety Improvements section.

Simpson Building Supply Co. spur

Decades after logging activity ceased in Totem Lake, Simpson Building Supply Co., a division of Simpson Timber Co., announced in February, 1967 that it intended to construct a new wholesale distribution warehouse at 12249 NE 124th Street, also known as the “Five Corners” area, to be managed by Orville Pearson, previously in charge of Simpson’s Wichita, Kansas branch. President C. H. Bacon Jr. credited “rapid truck transportation over new freeways” with Simpson’s decision to become a major lumber supplier in the Seattle area. Simpson intended the facility to link “lumber, plywood, softboard, and door plants in Shelton and McCleary with Seattle area building materials dealers”. More details were revealed in May, including that the facility would replace the recently-purchased Spokane Street warehouse in Seattle of Elliott Bay Lumber Co.

In early May, during construction of the building, Simpson requested a spur be installed. The NP approved the proposal that same month and the spur went in service on July 1, the same day that the warehouse opened. The spur was approximately 500 feet long and was very near the long-since-removed Neel / Woodland Shingle Co. spur, but on the opposite side of the main track. The former Simpson spur survived until the end of active railroad use and the building exists in 2018 as Public Storage.

Business expanded for Simpson soon after opening. In March, 1969, the firm added equipment to pre-stain lumber and plywood. Two years later, in March, 1971, the firm announced that the Kirkland location, under the direction of Ken Pottenger, would manage all of the firm’s Washington distribution centers, in Kirkland, Everett, Moses Lake, and Shelton.

A Burlington Northern SPINS document from 1978 indicates that 1 car could be spotted on this spur. (The BN instituted the Shippers Perpetual Industrial Numbering System, aka SPINS, in the 1970’s.)

Simpson closed its doors in approximately 1984. Public Storage took over the building soon after and still operates at that location today. We assume the spur was removed sometime shortly after Simpson’s closure.

The primary sources of information that informed this work stop in the mid-1970’s. If you can help tell the history from 1975 – 2009, please contact us!

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

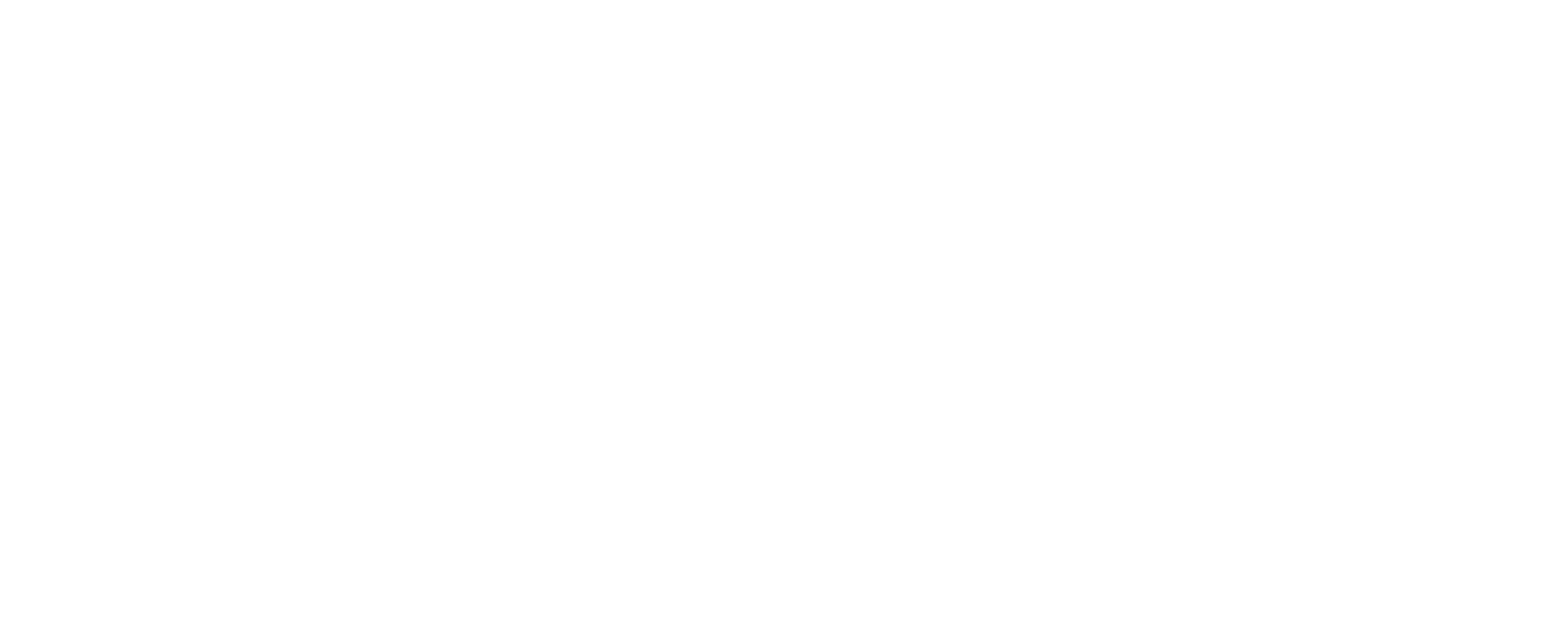

Totem Lake Connector

On July 8, 2023, Kirkland residents celebrated the opening of the Totem Lake Connector, a $22.3M pedestrian and bicycle bridge over NE 124th St. and Totem Lake Blvd. Scroll or swipe below to see various views of this impressive engineering project.

This bridge provides a long-term solution to the difficult traffic problem posed by two grade crossings within feet of each other, on two of Kirkland’s busiest thoroughfares—a problem with which the NP and BN had decades of experience. (Photos taken on October 5, 2023 by Matt McCauley)